The following account of the discovery of Tahiti on June 19, 1767, is based on the complete journal of George Robertson, Master on board the H.M.S. DOLPHIN, with excellent explanatory foreword and editing by Hugh Carrington, and the journal of Captain Wallis as re-written by John Hawkesworth in 1773.

TAHITI

AND THE SOUTH PACIFIC

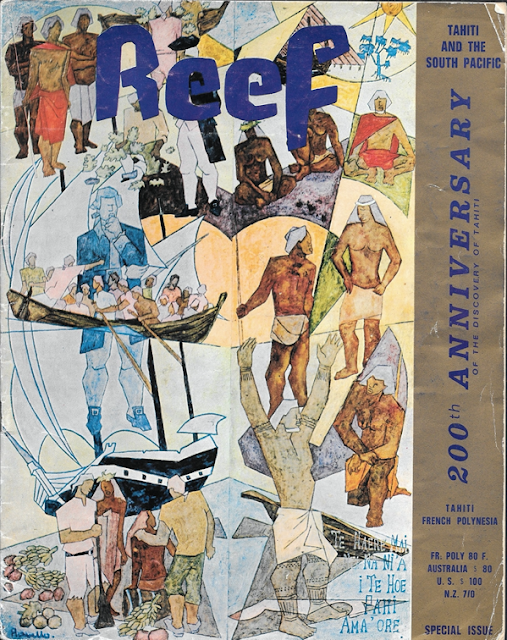

Reef Magazine

Vol 2, No. 3, 1967

Special Issue - 200th Anniversary of the Discovery of Tahiti

"Wallis Discovers Tahiti" by Tracy Laignelot

30 Pages: 21-27, 34, 37-38

Reef [Magazine], Vol 2. No. 3, 1967 - Special Issue

200th Anniversary of the Discovery of Tahiti

Publications Reef, S.A.R.L., B.P. 966, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia

October 2020: This account was researched and written in Tahiti by Tracy Laignelot in the 1960s when she lived on the island for close to 9 years. Her name is now Tracy Novinger and she is the author of 3 books published in 2001, 2004 and 2018 respectively. Her fourth book, a novel set in Tahiti, is scheduled for print and Kindle in 2022.

To Find the Southern Continent

His Majesty King George III succeeded to the Crown of

England in 1760 at the age of twenty. The young king was

intelligent and well-educated, and altruistically ambitious to

use his powers for the benefit of England and of humanity in

general. One of his greatest ambitions was to achieve the

exploration of the unknown parts of the world. He was the

catalyst setting off the great activity in naval exploration that began in the latter half of the eighteenth century and was

continued in the nineteenth century.

After the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, the English

Admiralty adopted and only slightly modified plans for exploration by Sir Francis Drake, which were nearly 200 years old.

The first voyage was to have as its main object discovery of

the Pacific entrance to the Northwest Passage, and the second

projected voyage was to explore the South Pacific.

By reading into the reports of the early navigators more

than the writers had intended, all idea of the ultimate content

of the vast unknown spaces of the Pacific Ocean was based

on the existence of a great continent, in a temperate climate,

nurturing a population with whom the initiation of commercial and social intercourse could only serve the good of mankind. This theory was strongly supported by scientists who

pointed out that it was not only reasonable to expect that the

southern hemisphere should contain as much land surface as

the northern, but that a great land mass was essential for the

dynamic stability of the globe.1 The Admiralty were as much deluded by this popular theory as scientists and writers, and instructed Wallis to:

"proceed with the Dolphin and Swallow round Cape Horn or through the Strait of Magellan, as you shall find most convenient; and stretch to the Westward about One Hundred or One Hundred and Twenty degrees of Longitude from Cape Horn, losing as little Southing as possible."

They were confident that he would have found the coast of

the Southern Continent long before he had sailed so far and

gave him detailed instructions for surveying the coast discovered, dealing with its inhabitants, and taking possession.

Two ships were fitted out for Wallis' expedition: the Dolphin, a 32-gun frigate with a complement of 150 men, commanded by Wallis himself, and the Swallow, a 14-gun sloop,

with a complement of 90, commanded by Captain Phillip

Carteret. The two ships were to make notable if largely independent voyages, their tracks diverging after leaving the

Straits of Magellan.

The passage of the Dolphin and the Swallow through the

Straits of Magellan was one of the most difficult on record.

The Dolphin was finally obliged to leave the unseaworthy

Swallow behind, as the latter was not able to maintain the

speed that the Dolphin needed to break out of the Straits.

Thus the Dolphin sailed on into the Pacific Ocean alone.

The Dolphin was classed as a sixth-rate, and was one of

the earlier types of the "true frigates." Her length was 130

feet, and her greatest beam 34 feet. For the crew t here was

an area of about 1,500 square feet fur all living purposes:

slightly more than 12 square feet per man for a voyage of

two years. Obviously in such crowded quarters there was little

comfort or privacy for anybody. Yet on the whole the men thrived on it--even enjoyed it.

The Captain, Samuel Wallis, was a Cornishman, just 38 years old. Although a sound seaman and typical of the best

class of naval officer, Wallis had no particular qualifications

for the work of exploration and is not to be noted for either his enterprise or intellectual curiosity.

George Robertson, master of the Dolphin, was the author of a very interesting journal. The master of a ship in those

days was in a curious intermediary position--a relic of the

days when the captain was a military person whose duty it was to fight the ship while that of the master was to sail her.

Depending upon the character of the captain, the master

was more or less powerful and important. Usually, at that

date, his knowledge of navigation was better than that of

the officers.

Both Roberson's calligraphy and his style of writing for the

times indicate that his education was above the average. His

constant references to the living conditions and health of the

sailors, his expressions of anxiety for the Swallow and his

criticisms of his fellow officers reveal him as observant and

as sympathetic. During the circumnavigation the continued

sickness of the Captain and First Lieutenant Clarke threw all

the executive and administrative responsibility upon the

shoulders of Furneaux, the only other officer, and Robertson.

The successful outcome of the voyage can be attributed to

the skill and conscientious devotion to duty of those two.

Comparison of their literary ability places Robertson as

superior to Furneaux. On his efficiency there is no need

to comment! 4

Round the Cape to the Southern Sea

The Dolphin left England on August 22, 1766, and passed

the Straits of Magellan in late April of 1767. After weeks of

sailing, scurvy had become a source of main concern to everyone on board. On May 28th Robertson reports:

"The Wind from E.N.E. to N.N.E. a Moderate Gale and fine Clear weather- this Day we saw a very Great Bird about the size of an Albetross... we likeways saw several flying fish and some tropick Birds- this gave us all great hopes of Seeing some happey place soon where some sort of refreshment can be hade, our Seamen was now falling doun in the Scurvey Wing fast, the Capt and us spears as much of our fresh stock as posable to the Sick, but it now begins to run Short... since the people has been at 1/3 allowance they have left no Bargo nor peas for the poor Pigs, which Makes the poor sick and us to fear the worse--the Greatest Blessing we Enjoyed all this time was fine weather and plenty of Water..."5

One can imagine, seven weeks after leaving the Straits,

on low rations and being afflicted with scurvy, the emotions with which the crew of the Dolphin finally sighted land on

June 7th--it was the atoll of Pinaki. There were no inhabitants, but "scurvy grass" and coconuts were gathered and

brought on board.

The Dolphin sailed on and reached Nukutavake the next

day, and of their first brief encounter with Polynesians, who

were in canoes, Wallis said:

"The inhabitants of this island were of a middle stature and dark complexion, with long black hair, which hung loose over their shoulders. The men were well-made and the women handsome."6

Between June 11 and June 18 the Dolphin came alongside Vairaetea and sighted Manuhangi, Nengo-Nengo, and,

finally, Mehetia, which is only 60 miles off the coast of

Tahiti and is the most easterly of the Society Islands. Some

provisions were obtained on Mehetia and then the ship

moved quickly on to try to find what they thought was the

high land sighted the day before.

The Day of Discovery

On June 19th, 1767, the magnificent mountains of Tahiti, island hitherto undiscovered by Europeans, could be plainly seen. There was great excitement on board at the prospect of visiting this new land, though the crew of the Dolphin did not realize what they had discovered or that this place would come to be called Paradise by men all over the world. Robertson expressed what must have been a mixture of excitement, relief, and awe as he viewed what he thought was the object of the Dolphin's voyage:

"We now suposed we saw the long wishd for Southern Continent, which has been often talked of, but neaver before seen by any Europeans."7

As Wallis did not want to be embayed in the recesses of the supposed continent, he ordered the Dolphin to head for the northernmost land in sight. Night fell, but at 2:00 A.M. the sails were again set. At sunrise they headed straight for the land. It was a hazy day, and as it cleared, the eastern- most point of Tahiti was seen bearing north at six miles. More than a hundred outrigger canoes already lay between the ship and the foaming white line of breakers demarcating the reef.

The speed with which news travels in Tahiti is incredible--as if by "coconut radio"--and soon the whole island was

aware of the arrival of this strange vessel. Strangely enough

the Tahitians had been forewarned of this visit by a prophecy passed on by oral tradition:

An old prophet named Pau'e who was well known in Tahiti had said one day, "The children of the glorious princess will arrive in a canoe without an outrigger and covered

from their feet to their heads." To the skeptical he demonstrated how a wooden bowl would float upright without an

outrigger when properly balanced with stones. He died three

days later and some time afterwards the Dolphin arrived. The

Tahitians cried: "There is Pau'e's canoe without an outrigger

and there are the children of the glorious princess." Pau'e also predicted with striking accuracy that a new king would eventually come to govern the Tahitians and new customs would prevail in Tahiti. Bark cloth and the mallet to beat fibers would no longer be used and the people would wear different and strange clothing.8

The men on board the Dolphin made friendly signs at each other, the crew holding up trinkets and

the Tahitians the shoot of the banana tree. This meeting was

marked by a fifteen-minute speech with the Polynesian love

of oratory and then the shoot of banana tree was thrown into

the sea. The sea was considered a large temple sacred to all,

and the shoot represented man. The Dolphin crew understood

that friendly signs were being made; even though the symbolism necessarily escaped them. And when the Tahitians

called to them, "this is Tahiti," they understood the phrase

as one word and recorded the name of this new land as

"Otaheiti."

Finally one of the bolder young Tahitian men climbed up

the mizzen chains and jumped onto the shrouds. He descended

to the deck after many entreaties, but would not accept any

gifts until some other Tahitians came on board. The Englishmen tried to make them understand that they wished to trade for provisions.

At this point a goat, charging from the rear, butted one of

the Tahitians in the posterior. Wheeling around he saw the

strange animal about to butt him again. His reaction to this

unexpected and strange attack was to leap overboard, and

all the Tahitians followed him as if by instinct. They all

returned shortly after the initial shock of surprise wore off.

By signs they made the Englishmen understand that they had

pigs and chickens, but had never seen goats or sheep.

As the canoes more closely surrounded the ship, the Tahitians on board became very bold. They tried to pull iron fittings off the ship and one Tahitian grabbed a new laced hat

from the head of a midshipman. To make them all more wary

a nine-pound shot was fired in the air. It was temporarily

effective. The Tahitians on board dove into the water and

swam to their canoes, and all the canoes moved off about a

hundred yards. A musket was pointed at the hat thief, but

this did not concern him as he didn't know what it was.

The canoes began to move in again, so the Dolphin made

sail and moved out of reach. Damage would have had to be

done to make the Tahitians respect firearms and Wallis did

not want to do so without provocation.

The frigate sailed on to the West following the coast and

the Englishmen thought it the most beautiful country they

had ever seen. Even Wallis praised it and described it as

having ''the most delightful and romantic appearance that

can be imagined: Towards the sea it is level, and is covered

with fruit trees of various kinds, particularly the cocoa nut.

Among these are the houses of the inhabitants, consisting only

of a roof, and at a distance having greatly the appearance of

a long barn. The country within, at about the distance of

three miles, rises into lofty hills, that are crowned with wood,

and terminate in peaks, from which large rivers are precipitated into the sea. We saw no shoals, but found the island

skirted by a reef...which there are several openings

into deep water."9

Robertson noted as they sailed along the coast, "This appears to be the most populoss country I ever saw, the whole

shore side was lined with men, women and children all the

way that we saild along...we was now fully persuaded that

this was part of the Southern continent."10 At the sight of

the lush vegetation he further comments, "This ought to be the Winter Season here if any such there be--butt there is not the least Appearance of it to be seen, all the Tall trees

is Green to the very tope of the Mountains."

The Dolphin was running up the eastern and northern side of the island of Tahiti, and on the 21st of June soundings were made at the mouth of the Papenoo River. Good anchorage was found with seventeen fathoms and a fine sandy bottom. The Dolphin ran in and anchored about two miles from shore. Though there was enthusiasm on board over the good harbor found, and also at the prospect of visiting this "fine beautiful country" (especially after so long at sea), some of the crew were fearful because of the great number of Tahitians and talked of sailing on to Tinian. If they had sailed on, however, not only would they have missed visiting these tempting shores, but the crew would have undoubtedly arrived in great distress due to scurvy.

Blood in Tahitian Waters

Outrigger canoes came from the shore bringing coveted

coconuts, fruits, fowls, and pigs to trade, but all too often the

Tahitians would accept payment and then keep what had been

paid for, too. When Mr. Robertson took two boats out to sound

at this first anchorage, sailing canoes followed so closely that it

made sounding impossible. The ship's boats also made sail and

ran in toward shore, Robertson thinking to profit by at least

spotting a convenient place to later fill water casks. Finding

that they were surrounded by some 200 large and small outriggers, and that some Tahitians were trying to board their boats,

Robertson thought it more prudent to tack and return aboard

the Dolphin. Outriggers tried to ram them, and simply firing

muskets did not help, for though the noise startled them, the

Tahitians found they were not hurt. Robertson finally was

obliged to order his men to fire at two of the more insistent

aggressors: one was wounded, one killed, and both fell into

the water. When their companions pulled them back into the

outrigger canoes, they discovered that muskets not only made noise, but caused strange wounds. The news spread from

canoe to canoe, upon which they all dropped back and returned toward shore.

The next day the boats were able to sound without being

bothered by canoes. Many Tahitians assembled on the shore

to watch them, and motioned for them to land. Among them

were young women who were insistent to the point of undressing and trying to convince the men to come ashore by "many wanton gestures the meaning of which could not possibly be

mistaken."12 If the Englishmen were tempted by such uninhibited invitations, they were prudent enough to decline them--especially since it would not be possible to land at this spot

without getting the muskets wet.

Wallis considered the fact that canoes did not hesitate to

return shipside again to trade, even after two Tahitians had

been shot, proof that the Tahitians realized that they had

brought the disaster upon themselves and had nothing to fear

as long as they provoked nothing.

For trade the Tahitians much preferred nails to anything

else, even though they did accept beads, knives, and other

such articles. On June 22nd, market prices were about a

twenty-penny nail for a hog, a ten-penny nail for a roasting

pig and a chicken or a bunch of fruit could be had for a

sixpence or a string of beads.

Breadfruit

Successful trading was carried out, and breadfruit, plantains, "a fruit resembling an apple only better," chickens, and enough pork to serve the ship's crew a pound apiece for two days, were obtained.13 The water on board was running very short, and still no landing had been made. Wallis sent boats out with water casks, but as the men did not dare land, they made signs to ask the Tahitians if they would fill them. They did so willingly, bringing back two casks with water and keeping the rest for their trouble. Requests the next day for the casks to be returned were to no avail, or were threats, and another attempt to get water yielded on about 40 gallons.

The "Dolphin" Strikes a Shoal

A conference with Captain Wallis and First Lieutenant Clarke, who were too sick for duty on deck, resulted in a decision to sail the Dolphin around the next low point (Point Venus) into what is now known as Matavai Bay. There the ship might be able to anchor close to the mouth of a river flowing into they bay and fresh water could then be easily procured. Robertson and the men in the boats, who were to

sound for good anchorage and report back, were surprised to

see the Dolphin following them closely. One boat was reporting twelve fathoms, but Robertson was signaling the ship to

stand off as he was finding only three. Just as she approached

between the two boats she struck and stood fast on a shoal,

swiveling round on a rock with her stem in towards the shore.

To Robertson it appeared that she was going from one tack

to another and he kept on sounding. By the time he returned

aboard she was striking hard with all her sails shaking

against the masts.

The sick Captain and First Lieutenant were already on

deck to give orders. Sail was ordered clewed up as fast as

possible. The launch was sent out with stream cable-and

anchor. Perhaps anchor could be dropped outside the reef so

that the ship could be drawn off the shoal. But in Tahiti,

typical of South Pacific islands, the bottom drops away vertiginously outside the reef and no bottom could be found.

Everyone froze on board the Dolphin, listening to their ship

pound heavily on the shoal. Outriggers hovered around the

ship as if waiting for the end. The crew was surely acutely

aware that if their vessel were to sink in this undiscovered

part of the world, their chances of ever seeing England again

were remote, if not non-existent. Suspense drew nerves taut,

but then relief was brought as the breeze veered and sprang

up from the shore. All sail was made, the ship inched slowly

forward, and then slid off the shoal to float freely in deep

water once more. No sooner was the ship free than the wind

freshened--it would not have taken long for the high surf

to pound her to pieces had she remained fast. Running a long

easy mile out to sea the pumps were drawn; the Dolphin was

making little more water than usual.

When a second attempt at anchorage in Matavai Bay was

made, sounding was carefully made and a good sandy bottom

with a hundred feet of clear water found. At signs of belligerence from watching Tahitians during the preliminary

maneuvers of the ship's boats, any clash was prevented by

warning shots fired from both ship and boats. The ship was

safely anchored and a little trading done alongside. At sunset

the crew was divided into four armed watches as a precautionary measure, for relations between the Tahitians and

Englishmen were still to be defined. It was a fine tropical

night. No outriggers were seen near the ship, but Tahitians

carrying lights could be seen walking along the reef to

spear fish.

At sunrise, as the crew began to warp the Dolphin up the

bay to another anchorage, about 300 canoes gathered around

her. To insure disciplined trading, Wallis entrusted all buying of provisions to the gunner and two other men. Most of

the trading canoes carried a young girl who would undress

and make inviting gestures. Soon another 200 or so canoes

arrived. To Wallis's concern these carried almost nothing but stones, and the Dolphin was now surrounded by more than

500 canoes carrying nearly 4,000 Tahitians. A large double

canoe signaled for permission to come alongside and consent

was given. A tuft of red and yellow feathers was presented to

Wallis who, thinking it a gift, accepted and went to get gifts

in exchange. Actually, the tuft was intended to hex the visitors, thereby insuring victory to the Tahitians, and when it was accepted a coconut frond was raised to signal attack. This was more than an incident or small clash. With shouts the Tahitians launched a shower of stones, some using slings and stones large enough to do considerable damage. Even though a canvas awning against the sun afforded some protection to the crew, men were cut and bruised.

The Violence Ends

Wallis decided to retaliate with arms, for much of the

crew was sick and feeble. The canoe from which the signal

for attack had come was pointed out and it was smashed in

two. Muskets, grape-shot and round-shot were devastating.

Another 300 large canoes that rallied near shore and headed for the Dolphin were allowed to approach within three or

four hundred yards when the three-pounder loaded with seventy

musket balls immediately dispersed them. Though the shores

of the bay and the tops of the surrounding hills were full of

men, women, and children as audience to the skirmish, by

noon not a spectator or an aggressor was to be seen. The

Dolphin stood prepared to fend off any new attack, but the

afternoon and night passed without incident.

In the morning Wallis decided to claim possession of the

island of "Otaheiti"--it had been in some manner realized

by this time that this was not a "southern continent". Protected by men in boats, Furneaux found good landing and

went ashore to claim Tahiti in the name of King George III.

Everyone drank to the King's health and a pennant was

put up.

Meanwhile, some four or five hundred Tahitian men had

been slowly approaching on the far side of the river, carrying

banana shoots before them. Two old men placed themselves

in an attitude of supplication, and one crossed when signs

were made for him to do so. He brought a small pig and a banana shoot as gifts. He seemed to understand when Lieutenant Furneaux indicated that the shooting had been provoked by the Tahitians, but did not concede it. Several other

Tahitians at length ventured across the river to trade fruit

and pigs.

The boats returned to the Dolphin with casks of good water

obtained easily from the river. All the Tahitians then crossed,

but seemed to fear the flying pennant. Robertson watched

them through his spy-glass and saw a few approach and fall

to their knees to make some kind of incantation. Banana

shoots were then placed by hundreds of Tahitians at the foot of the pole.

Shortly before sunset the two old men brought a pair of hogs, placed a banana shoot near the pennant, then carried

the hogs to a canoe and brought them to the Dolphin. Each

made a long speech, threw banana shoots in to the sea, and

made sign for ropes to be thrown to take the hogs. They

would accept nothing in exchange but orated further and

pointed to the pennant. It was later realized that they were

requesting permission to take the pennant, for this is what

they did upon landing.

After dark, large fires were seen burning on the sides of

hills. At six in the morning again not a Tahitian could be

seen on shore and nearly three tons of water could be taken

on board. Soon, though, they appeared, armed with spears

and clubs, and one carried the captured pennant flying at

the end of a long pole. A number of large canoes advanced

round the western point of the lagoon. Thousands of men

were in the woods, and stones were piled up along the riverside. The captain decided to take decisive action, as the

shortest conflict would do the least damage to all concerned.

He ordered his men to fire first on the grouped canoes. They

either retreated back around the point out of sight, or made

for shore where the men ran for the woods. Boats were sent and some eighty canoes on the beach destroyed with axes to

prevent them from being used again. Shots were fired into the woods

and at the hill; one almost reaching the Tahitians at the summit. The prompt and devastating retaliation with firearms by

Wallis put an immediate end to this final and decisive battle.

A Peaceful Interlude in Paradise

The battle over, men and women began slowly to appear on the beach to the north of the river, planting banana shoots in the sand and leaving gifts as a peace token. There were dogs, pigs, chickens, fruit and white bark-cloth. They made signs to the ship to send men ashore for the gifts. On board, the Englishmen were intrigued by the sight of the dogs, which had their forelegs tied up over their heads and would rise to run short distances on their hind legs. They thought them some strange new animal. A small landing party came for the gifts. They took everything, but released the dogs, not knowing they were for eating, and left the barkcloth, of which they did not want to deprive the Tahitians. Gifts were left as a return gesture of amity, and the Englishmen returned to their ship.

On board, they waited for their gifts to be accepted, but the Tahitians would not take them. After a while, someone ventured that the cloth must also be taken to show that the Englishmen completely accepted the gesture of peace which had been made. A party returned for the cloth, and the Tahitians then took the gifts left in return. Intentions of future amicable relations were mutually made understood and further trading envisaged. It was made clear that the Tahitians should come in small numbers and keep to the far side of the river; the visitors were to keep to theirs.

Those in the landing party were quick to notice some very attractive Tahitian girls who were present at this meeting; some light copper, others darker, and some almost fair. Noticing the interest aroused, a few older Tahitian men drew several of the girls forward and stood them in a row. They indicated that the Englishmen should choose, and as many as they wished. In case the purpose of this offering were not understood, they made signs showing what to do with the girls. The men did not really need any directions, and indicated to the girls that they were not ignorant in that respect. The Tahitians seemed delighted at the extremely enthusiastic response obtained, but the girls a bit intimidated.

The officer with the landing party could not accept to bring any of the girls on board and ordered his men into the boats and back to the ship. The boats' crews swore that they had never seen finer-made women in their lives and declared to a man that they would rather live on two-thirds rations than lose the opportunity to be had on shore. All on board became rather keen to land and even those who had been on the sick list for weeks found sudden energy. They seemed to be certain that the young girls would make excellent nurses and speed their recovery more than the ship's doctor ever could.

Hostilities seemed finally to be over and Wallis ordered that every man was to have as much fruit and as many coconuts as he wanted and pigs were to be killed to make broth for all hands on board. The crew, in improved health after a week at Tahiti with better food, and now with stimulus to their morale, passed the night merrily at the thought of going ashore and making "friends" with the Tahitians.

The next day the crew industriously painted the ship, and repaired and dried the sails. No Tahitians came to trade, but could be seen removing, with caution still, the least damaged of the double canoes on the beach.

The second day after the final battle, while water casks were being filled at the river, some 200 Tahitians appeared on the far bank with fowls and fruit to trade. The seamen noticed earrings in the women's ears, but could not tell from a distance what they were made of. They were curious about these, speculating whether valuable pearls or stones were to be found on the island. Wallis, however, had given strict orders that no Englishman was to cross over to the far side of the river, and that not more than two or three Tahitians be allowed to come over at a time.

Only the old man who had been the first to cross over the river was allowed to come and trade, but through just one person it was impossible to obtain even a tenth of the provisions available.

With relations more stable, the ship's doctor told Captain Wallis that the sick needed to go ashore every day if they were to regain their health. A tent was to be pitched for the most ill, and a cutlass was given to each of the more fit, just in case protection might be needed. They were told not to stray from the vicinity of the gunner who had been charged to carry on trade. The sick seamen began to recover rapidly, but Wallis himself became extremely ill, and at one point it was even feared that he might die.

Trade began to fall off so much that salt provisions had to be served on board again. Many of the Tahitian men and women who came with provisions would not trade through the old man, apparently because they were of a higher rank than he. When the gunner allowed each person to do his own bargaining, trade immediately picked up again. Even some young girls brought chickens to trade, and they were received most cordially by the seamen who encouraged them to continue to come by gifts of beads and earrings. They gave the men a "signal" which would have been obeyed with alacrity, but unfortunately for the men they were ordered back on board the Dolphin before they could comply.

July 6th marked the beginning of a new trade with Tahitians or, to be more exact, an "old trade." Robertson recorded that a "Dear Irish boy, one of our Marins was the first that began." The dear boy received a severe beating from the other men on liberty for not beginning in a more proper manner--they thought he should at least have gone behind a bush or a tree. "Padys Excuse was the fear of losing the Honour of having the first,"14 and he apparently took action on the spot when the opportunity was presented.

"Dolphin"Visitors

On the 7th Wallis left his bed, as he was finally feeling

better. He hardly recognized his crew, all the men looked so

healthy. He was grateful for not having ever been troubled

with any problems or complaints while ill; everything had

been worked out as well as possible, sparing the sick Captain

any concern. He decided to go out for an airing with Robertson in the barge. They made some soundings in the southwest

part of the bay, and rowed back along the shore to look

around. They came upon a marae, and Robertson accurately

supposed this structure of stone walls and platforms to be a

place of worship.15 They could see images carved out of tree-trunks and were very much intrigued. They did not land however, as there were many Tahitians watching and they weren't

sure whether they would be welcome at this place. The Captain returned on board in time to observe an impressive arrival of sailing outriggers with colored streamers--they were bringing the chiefess Purea to Matavai Bay from

the district of Papara.

Later, Robertson and two young men finally ventured on

a walk along the shore and back into the countryside. The

Tahitians appeared to be pleased to see them, and they were

able to circulate freely and observe everything they wished.

Most of the houses were constructed mainly from the coconut tree, with trunks for supports and woven fronds forming

high thatched roofs over a cool and shady interior. There was little in the way of "furniture"--woven mats were used

for sleeping and in the way of utensils Robertson saw coconut shells for drinking, gourds, wooden trays, etc., and on

this occasion he was able to look closely at wooden images, carved

one on top of the other. Though not finely made, there was

absolutely no mistake to be made as to the sex of each human

figure--nature was very exactly imitated. The Tahitians did

not mind when Robertson touched the carvings, but would

not touch them themselves. It is thought that the images were

regarded as representations of gods that intermittently inhabited them, or as vehicles through which requests could be made.

The Tahitians were a strong, well-built people, handsome and active, and very clean. The women averaged from about 5' to 5'6" in height, and the men from 5'7" to 5'10". The Englishmen remarked that those of high rank were usually taller than the average and lighter in complexion. Dark-skinned people seemed to be about ten times more numerous than those of a medium complexion, and the medium-skinned about ten times more numerous than the very light.16

The Tahitians cared for their skin and hair with coconut oil, often scented with the tiaré flower. Their hair was neatly groomed and usually black, although often brown or reddish, and in children it was often sun-bleached almost blonde. It was usually tied in one or two bunches, however women wore their hair curt short on their neck.

To work, men wore a type of breech-cloth and both men and women wore a pareu wraparound for leisure at home.

The tiputa, a type of poncho, was worn to go out. The people's

ordinary clothing was brown and made from the bark of the

paper mulberry; for those of high rank and for special occasions, beautiful white garments were made from the bark of the breadfruit tree.17

Children usually went naked until the age of six or seven and at puberty both sexes began the operation of tattooing which would take some eight to ten years to complete.18 The intricate work was extremely painful, but endured willingly as the price of beauty. The blue designs and patterns were chosen according to a person's taste and almost any part of the body was tattooed. Women usually tattooed their hands, feet, and hips, and men their arms, legs, thighs and buttocks; in fact, some men were practically covered with tattooing.

The island was surprisingly devoid of mammal, reptile,

fowl,. and insect life, though the Tahitians had dogs, pigs,

and chickens. Robertson astutely supposed they had brought

these with them on migration from a continent.19

After this first leisurely walk through the lush vegetation

of Tahiti's shore, Robertson and his companions headed back

to return on board the ship. On their way back they were stopped with smiles by three "very fine Young Girls," one of

whom made a sign to Robertson. Not understanding, he inquired of his companions what she meant. They looked rather

grave, and told the Master that they weren't sure. Robertson

supposed the girl had something to trade, and naively motioned for her to "show her goods, but this seemed to displease

her." Another girl repeated the sign:

"She heald up her right hand and first finger of the right hand streight, then laid hould of her right wrist with the left hand, and heald the Right hand and first finger up streight and smiled then crooked all her fingers and keept playing with them and laughed very hearty"

at which Robertson's companions could not keep from laughing with hearty good humor also. When Robertson insisted that his companions explain, they supposed that the girls wanted nails, but begged to be excused from explaining the rest. Conscientious Robertson good-naturedly gave each of the girls a long nail and waved a friendly good-bye.20 Thus the price of the Old Trade was unknowingly fixed at a thirty-penny nail each time.

A Market for Nails

This Old Trade was becoming a problem, as it had begun to spoil the trade for provisions. After a conference on board, it was decided that the men be deprived of liberty in order to protect market prices. This made well men look ill, and the ill look even worse. The doctor said that what was bad for the men's morale was bad for their health, and the men readily agreed. He furthermore added "upon his Honour'' that no man on board was affected with any disorder communicable to the Tahitians.21 So it was decided instead to try to keep the men from carrying nails ashore.

On July 10th a man appearing to be a chief, about thirty,

well made and handsome, was invited aboard. He was very

observant and seemed surprised at the ship's construction. This was the first day that the Captain and First Lieutenant

were both able to sit up and they all dined together in the

gun room with their guest. He picked up and carefully examined the plates and silverware but when he saw dinner served

laid them down. He carefully watched and imitated their

manner of eating. He did not care for alcoholic beverages,

preferring water. He seemed disturbed at not having a pocket

handkerchief to wipe his mouth on as the others, and Robertson had him use the corner of the tablecloth to set him at ease.

This so shocked the finicky Mr. Clarke that he stopped eating

and scowled and scolded the chief. To save his feelings, Robertson "hobernobd" with the chief, and used the corner of the

cloth himself. This pleased him and he made signs to the

irascible Clarke that he would bring a fine young girl for him

to sleep with. This put an immediate end to his "growling"

and Clarke said "well done Jonathan." This was the first

Christian name used for a Tahitian, and he was thereafter

called Jonathan.

Jonathan kept his word and later brought two young girls

on board and offered Clarke his choice. His acceptance or

refusal is not recorded, but it would seem that they made

other friends on board. Jonathan was dressed in a whole suit

of clothes, including shoes. When he went ashore, he made

his friends carry him so as not to wet his shoes. He disappeared

and was not seen again; perhaps his friends were afraid he

might eventually leave with the Dolphin, so taken was he

by everything on board.

By this time the Tahitians and seamen were very sociable,

"espetially the young Girls who very seldom faild to carry off

a nail from every man of the party." On one visit ashore, one "Gentleman of the party" met a very handsome woman, to

whom he made presents on several occasions, but never received the usual signal. One day it came, though, and she led

him to a house, but just then a well-built man came up and

the woman disappeared i n the house and quickly returned

wit.h a fowl and fruit and pretended to bargain with the

Englishman. She acted hesitant about the double price offered,

but the presumed husband quickly accepted. The Englishman,

seeing the man was a carpenter, give him several nails, and

the man's heart was won. He would have given the Englishman anything he had (except his wife). He returned unhappily to the ship, and was consoled by his mates who thought

that he was lucky to have escaped a good beating had he been

caught trading for something else.

The handsome little woman came to visit her "Gentleman"

friend on board bearing gifts, accompanied by her husband

and three other women. The husband was very interested in

the furniture, and measured all the different dimensions, recording them by making knots on a piece of line. Robertson

thought he would readily be able to construct a chair or table

after such careful observation.

Meanwhile, the friend tried to slip unseen into his cabin

with the woman, but the man saw them and joined them. This

cost the friend a suit of clothes to the husband and a shirt to

the wife, besides the trouble of showing the curious man everything in his cabin.

Finally, the woman slipped out of the cabin and cast their

outrigger adrift. Letting it get away for a while, she then

loudly called for her husband to save it. He started to jump in and a well-meaning person tried to detain him, intending

to go after it with a boat. But the woman got so excited and

carried on so that her husband twisted out of his detainer's

arms and dove in and swam after the canoe. The instant he was in the water, she grabbed her friend's sleeve and pulled

him into his cabin. While her husband rescued the canoe that

had somehow drifted away, she enjoyed the reward of her "Art and Cunning." The man was back with the canoe in

about ten minutes, and his wife presented him with a few

large nails gained in his absence. He was quite pleased, not

knowing how she had obtained them.

Two of the Dolphin's men, when out walking, were invited

to eat by a regal-looking Tahitian woman. It was Purea. They

reported that the meal lasted about an hour in all, and that

there were four or five.hundred persons present. All the Tahitians of high rank were served first (except Purea). These

recited a few words, threw a small portion of each dish on the ground, and then began to eat. Everyone else was served by

order of importance, but Purea was served separately. Three

special dishes were brought, and she invited the two Englishmen to partake of them with her. As they did not dare to eat

what had been prepared especially for the chiefess, they made

signs that they would prefer some fruit.

Two young women fed Purea, one standing on her right,

another on her left. They each fed her a bite alternately

using their right hands, washing them before and after each

bite in a bowl of clean water. Purea touched nothing with her

own hands. The two young women were in tum attended by

many other young women, and when everyone had eaten,

those who served ate at a distance. All washed before and

after the meal, and ate silently, at ease and in good humor.

Soon after, Purea came on board the Dolphin to visit,

accompanied by six high-ranking men. She was a tall and

handsome woman, about 5' 10", plainly dressed and without

adornment. The men with her were all dressed in white, also

without adornment of any kind, even though they had pierced

ears. Purea had a dignified bearing, and gave the impression

of a person used to commanding. She was very alert and

observant, and though she would neither eat nor drink on

board, was interested in visiting the ship. The cook's shiny

copper kettles impressed her, and the geese and turkeys onboard greatly interested all of the visiting group, for they had

apparently never seen such creatures before. Returning ashore

after her visit, Purea and the men accompanying her were

greeted by hundreds of Tahitians to whom she made a speech.

She must have been pleased with her reception on board,

because in addition to the livestock she had brought with her

as a gift, she afterwards sent some forty hogs and pigs, four

dozen chickens, and a great quantity of fruit to the Dolphin.

The Captain had a later opportunity to present her in return

with a pair each of the geese and turkeys.

Having remarked on Captain Wallis' and Lieutenant

Clarke's poor health, Purea invited them ashore for the good

it would do them. The group that went ashore to visit on

July 13th was greeted personally by the chiefess, and she had

Wallis, Clarke, and the Purser, who were particularly weak,

assisted as she accompanied them to a large building. There, on entering, some young girls removed the shoes, stockings,

and coats of the men who were ill, to chafe and massage their

skin with their hands. This hospitable attention to their health

and well-being was very much appreciated by the men. During the activity to make the visitors comfortable, the ship's

doctor, being very warm, removed his wig. The general astonishment was as great as if he had removed his head, but the

Tahitians quickly recovered from their shock and went on

with what they were doing. The visit ended and gifts of bark cloth were made to the Englishmen, who were then attentively accompanied back to their boats.

A concerned report from the gunner on July 21st indicated

that the Old Trade had risen about one hundred per cent;

Robertson began to wonder where all the nails came from.

T he carpenter was sent for and admonished to check his stock

of nails, and to take care that none were stolen. That afternoon when the liberty men were boarding the boat, the carpenter reported that every cleat in the ship had been drawn

and all the nails carried off. The boatswain at the same time informed Robertson that most of the hammock nails had also

been drawn and about two-thirds of the men were obliged to

sleep on the deck. Liberty was immediately stopped and all

hands summoned. No hand was to go ashore until it was

reported who had taken the nails and cleats, and what they

were used for. Their use was immediately made clear, for it

was common knowledge. Robertson told them that it was surprising that everyone knew for what the nails were used, but

not who used them. Some of the men reported that all men

on liberty carried on trade with the girls, so that prices were

rising; some girls were so extravagant as to demand from a twenty- or thirty-penny nail up to a forty-penny nail, or even

a seven- or nine-inch spike. It was also remarked that some

of the seamen were so extravagant that they spent two nails

on one visit ashore; this was justified by explaining that there

was such a great variety of "goods" that came to market that

purchases could not be resisted.

When the crisis was reported to the Captain, the culprits

were ordered punished, arid until they were denounced no

man was to set foot on shore. In the meantime it was possible

to carry out some successful trading for provisions.

By evening there was disquiet among the men, and among

themselves they condemned six scapegoats, for several declared

that a dozen lashes were preferable to having their liberty

stopped. The six condemned were supposedly picked ·on

grounds of having spoiled the trade by giving spike nails when

others only had a hammock nail. Three cleverly defended

themselves by "proving" they had gotten double value for

spikes. This degenerated into a general fight regarding the

respective prowess of different men, and Robertson was

obliged to impose order.

One fellow was finally settled on, with three concurring

witnesses against him. He was ordered to run the gauntlet

three times, but his mates, who were all as guilty as he, went lightly. When ordered on the second round he began to impeach some mates, thinking to get off, and for his trouble

got a beating that made Robertson excuse him from the third.

More severe punishment was promised, and no more liberty,

if any more nails or spikes were stolen.

On July 22nd, Purea returned on board the Dolphin with

an attendant and breakfast was served them in the Captain's

Great Cabin. Again, however, Purea neither ate nor drank

on board. She looked carefully at everything on another visit

of the ship, and when offered her choice of a present (from a mirror, wine glass, buttons, earrings, etc.), she preferred cloth.

She was given a ruffled shirt and shown how to wear it. Purea

then wanted the Captain to sign a Peace Treaty to settle all

differences, but the Captain claimed a disorder in his hand

and excused himself until some other time.

The chiefess took it into her head that Robertson must be

tattooed as were the Tahitians, and wanted to see his arms,

legs, and thighs. He showed her all, rather than disoblige her;

she was greatly surprised and had to feel his skin with her own

hands before she would believe that it was his skin. She then

wanted to see his chest which he showed her, and she was

astonished to find it full of hair (the Tahitians' bodies are usually hairless). She supposed he were strong and felt the

muscles of his thighs and legs which he flexed. She exclaimed

with admiration and called her attendant to feel them also.

She tried to lift Robertson and, when he resisted, could not

understand why she could not pick him up. Robertson then

lifted her and carried her round the cabin with one arm,

which seemed to please her greatly.

Eventually she made signs that she was returning ashore.

Robertson was to accompany her and to visit with her, but

not to remain any length of time as the Captain and Lieutenant were in such bad health. She was again received on

shore by hundreds of people and the most important were

made to shake hands with Robertson and the young man who

accompanied him. Robertson and Purea walked arm in arm, and upon arrival she made a speech to the many people who

met them. Robertson was invited to stay for a meal, but had

to decline. Even when an elderly woman proposed Purea, as

well as two other lovely girls for him to sleep with, he insisted

on going, but gave them to understand that he would return.

They visited many people on the way back, including two pretty girls, one of whom was lighter-skinned than Robertson himself. He took so much notice of her that it put Purea in a bad mood and she led him quickly off, taking him into no

more houses.

On the 25th of July there was an eclipse due. The Captain

instructed Robertson to observe it, which he did carefully from

shore. The latitude of Tahiti was established with great exactness for the Dolphin's records.

Finally, on July 26th and 27th, after over a month spent

off the verdant shores of beautiful sub-tropical Tahiti, preparations for departure were made on board the Dolphin. When

the Englishmen made known their intention of leaving at

dawn to Purea, she wept and entreated them to stay two

more days. Some of the crew were wary when she wept even

harder on refusal, thinking she might covet the ship or finally

want vengeance for the Tahitians that had been killed. Robertson believed from her earnestness that she wept only because

they were leaving and that it caused her great sorrow.

Since she was not allowed to spend the night on board the

Dolphin as she wished, she and hundreds of Tahitians slept

all night on the beach to be sure to see the Englishmen off

in the morning. They came alongside in canoes with many

more gifts, but Purea only wept and took no notice of the

gifts that Captain Wallis presented her in return.

Looking out over the many canoes, with the high mountains of Tahiti in the background, the seamen all agreed that they had never seen so many handsome people assembled at

one time.

It must have been with great regret on July 28th, at ten-thirty in the morning, that the first Europeans ever to visit a

now-legendary Tahiti sailed away on a light easterly breeze.

FOOTNOTES

1. Robertson, George, The Discovery of Tahiti (Ed. Hugh Carrington), Hakluyt Society, London 1948, p. xxii.

2. P.R.O., Ad. 2/1332, pp. 146-52. Quotation obtained from editor's

foreword to Robertson, George, op. cit.

3. Robertson, George, op. cit., pp. 20-34.

4. Robertson, George, op. cit., pp. 11-12.

5. Robertson, George, op. cit., pp. 111-112.

6. Hawkesworth, John, Cook's Voyages, Vol. 1, Strahan and Cadell, London 1773, p. 426.

7. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 135.

8. Henry, Teuira, Tahiti aux Temps Anciens, Publications de la Société des Océanistes, No. 1, Musée de l'Homme, Paris 1962, pp. 20-21.

9. Hawkesworth, John, op. cit., p. 435.

10. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 140.

11. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 141.

12. Hawkesworth, John, op. cit., p. 439.

13. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 146.

14. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 180.

15. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 178.

16. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 178.

17. Henry, Teuira, op. cit., p. 292.

18. Henry, Teuira, op. cit., p. 294.

19. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 178.

20. Henry, Teuira, op. cit., pp. 282-283.

21. Robertson, George, op. cit., p. 186.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Hawkesworth, John, Cook's Voyages, Vol. 1, Strahan and Cadell,

London 1773.

- Henry, Teuira, Tahiti aux Temps Anciens, Publications de la Société des Océanistes, No. 1, Musée de l'Homme, Paris 1962.

- Robertson, George, The Discovery of Tahiti (Ed. Hugh Carrington),

The Hakluyt Society; London 1948.

Comments

Post a Comment